Autistics on Autism

What everyone — especially professionals — needs to learn from autistic communities

Adapted and expanded from a talk I gave at the AVATAR Launch Extravaganza Professional Learning event on the 31st of March 2025.

I want to talk about three key theories developed by autistic people, all of which are really about people in general, but which are all needed by anyone who hopes to understand Autistic people in particular.

Neurodiversity describes the place of autistic people and others in society and the human population at large; the Double Empathy Problem describes how empathy breaks down between people with different perspectives; Monotropism describes autistic processing from the inside, in the context of a model of the mind as a system of interests.

Before I get into the details of these theories, I want to talk a bit about how we got here, because none of these ideas are new. Autistic people have been saying more-or-less the same things for decades, and although many people may be hearing them for the first time even now, elsewhere these ideas are already well embedded in practice.

History

It’s safe to say that autistic people have existed since before recorded history, but this year marks a century since the first clinical descriptions of autism, by the Ukrainian psychiatrist Grunya Sukhareva — who was writing about autism in girls and boys, around two decades before Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger. This April is the 55th ‘Autism Awareness Month’, although many prefer Autism Acceptance or — my personal preference — Autism Understanding.

Passive acceptance is not enough. If you have autistic people in your life (and there are a lot of us out there) you need to try to understand autism.

Fortunately, many autistic people have been working to explain our own experiences, for more than a third of a century now — so there is plenty to draw on! The earliest published ‘autie-biographies’ were Temple Grandin’s ‘Emergence’ (1986), and Donna Williams’ ‘Nobody Nowhere’ (1991). These were very personal stories, heavily influenced by the narrative of autism-as-tragedy that was so prevalent at the time, encouraged by professionals. When autistic people started talking to each other, a new narrative began to emerge.

Jim Sinclair met Donna Williams when she visited the USA to promote Nobody Nowhere in 1992, and together with Xenia Grant they formed Autism Network International — the world’s first organisation run by and for autistic people. In 1993 their newsletter, Our Voice, published Sinclair’s highly influential essay, Don’t Mourn for Us. Originally a presentation at the 1993 International Conference on Autism in Toronto, it was addressed primarily to parents, but its messages resonated with many of the autistic people who heard them. Indeed, they laid a foundation for much of what autistic people have been saying about autism ever since. This is one key passage:

Autism is a way of being. It is not possible to separate the person from the autism.

Therefore, when parents say,

I wish my child did not have autism,

what they’re really saying is,

I wish the autistic child I have did not exist, and I had a different (non-autistic) child instead.

Read that again. This is what we hear when you mourn over our existence. This is what we hear when you pray for a cure. This is what we know, when you tell us of your fondest hopes and dreams for us: that your greatest wish is that one day we will cease to be, and strangers you can love will move in behind our faces.

Our Voice was a paper publication, but within a year or two, the internet started allowing more and more autistic people to find each other, learn from each others’ experiences, and refine these ideas. Many found that the slower pace of email communication, and the absence of the nonverbal cues that so often cause confusion, suited their communication style. ANI started an email list called ANI-L in 1994; another was started in Europe, called InLv (for Independent Living) in 1996.

Meeting in person remained important. The idea of in-person Autistic Space was first formalised, or at least scaled up, with Autreat, the ‘retreat-style conference run by autistic people, for autistic people and our friends’ which started in 1996. Such autistic spaces have played a profound role not just in facilitating the sharing and development of ideas, but also allowing autistic people to be themselves — and to work out what that means, away from the fear of being misunderstood and rejected by neurotypical people.

In the UK, we didn’t get our own autistic conference/retreat until Autscape started in 2005, but there were many smaller-scale opportunities for autistic people to spend time with like-minded people from the 1990s on. My first experiences of autistic space were in my own home, although I didn’t realise it at the time. After she first formulated the theory of Monotropism in 1991, my mother, Dinah Murray, worked with and befriended many autistic people — including non-speakers she worked with as a support worker, as well as prominent self-advocates. She went to great lengths to connect people up, and ensure that people were listened to who might otherwise have been easy to ignore. Eventually, thanks to meeting people like this, we both realised we are autistic ourselves.

Informal networks and opportunities to spend time with other autistic people play a profound role in developing positive self-image and self-understanding for autistic people, and sharing coping strategies. With events like Autistic Pride, Autistic People’s Organisations like AMASE and AVATAR, and some of the better groups organised by service providers, many autistic people now get the chance to experience this for themselves, but sadly this is still not universal.

Neurodiversity

Once autistic people had the means to start finding each other, the autistic community collectively worked out the details of the idea that soon became known as neurodiversity.

Here is how I think about it:

Autism is a healthy part of the variability of humans

It’s not a disease, not something that’s gone wrong. Humankind is richer for having people who process the world differently, just as any ecosystem is richer and more adaptable with a wide range of species living in it. Diversity is a positive thing in general — even though it comes with challenges, and it’s not always easy being different from most of those around you.

Disability depends on the environment

The human world is rarely designed with the full diversity of human beings in mind. We don’t even design a lot of things to work properly with women, and they’re half of the population; autistic people are much rarer than that, and a great many things are designed in ways which are disabling for us. This can include aspects of the physical environment (like flashing lights and strong smells), but also the social environment (like expected ways of communicating, or unpredictable demands).

The social model of disability is an indispensable tool for understanding disability in general: the degree to which someone is disabled is not fixed. An accessible environment, with the right adjustments, can make an enormous difference.

Autistic thriving is worth pursuing

One of the reasons the once-dominant narrative of autism-as-tragedy is so harmful is that it ignores the many positive things about being autistic, while treating suffering and disablement as inevitable. Distress is not built into being autistic; it is always a response to something. Failure to recognise this has led to far too many autistic people having medical problems go unrecognised, and other avoidable sources of distress ignored. In many cases, responses to distress have been seen as ‘bad behaviour’ and punished as such.

None of this is inevitable. Thriving might not always look the same for autistic people as it does for others, and living a good life might be much harder when you’re disabled, but it is always, always worth pursuing.

Most autistic people don’t want to be “cured”

Autism is such a pervasive part of the experience of being who I am that a “cure” would mean replacing me with a different person. I actually quite like being me, even though I’m disabled in this society.

As with minority sexualities and gender identities, the quest for a cure, a way of making us “normal”, is fundamentally insulting and stigmatising, and has led to an array of harmful, abusive practices. Much better to work towards a world where we can be accepted as ourselves.

Listen to autistic people’s insights on autism!

Psychologists and psychiatrists, looking at autistic people from outside, have often misunderstood what they are seeing. This has led to diagnostic criteria which are a mix of distress behaviours, interpersonal difficulties (which we’ll come back to) and things like intense interests and sensory differences, which can be sources of great joy as well as inconvenience.

Autistic people are the leading experts on what it is like to be autistic — especially those of us whose ‘special interests’ include autism, and who have autistic friends, and who work with other autistic people. If you want to understand a foreign culture, you don’t just observe its people and draw your own conclusions without talking to them. You listen to people with first-hand experience.

Monotropism

Monotropism is a tendency towards intense interests, which may be lifelong or fleeting, but either way, they tend to be all-consuming in the moment. To look at it another way, monotropic people tend to have fewer interests aroused at any given time; they tend to be aroused more strongly, pulling in more of our attention, leaving relatively few processing resources for other things.

Monotropic people tend to enter ‘attention tunnels’, which can be sources of great joy when engaging with things we are passionate about; or unpleasant rumination, when we get stuck on things that have gone wrong. Entering and exiting attention tunnels takes time and energy — a big part of the reason for autistic inertia, and what is often described as ‘executive dysfunction’. Being wrenched out of an attention tunnel can be acutely distressing.

This processing style means that autistic people tend to struggle to master things which require attention to be divided, or switched rapidly between things. This includes neurotypical communication, which assumes that people are adept at communicating simultaneously with words, tone of voice, facial expressions and body language, in both directions at once, while keeping in mind the context of the relationship between speakers, and smoothly resolving frequent ambiguities in speech.

Misunderstandings frequently occur in both directions. Non-autistic people assume that autistic people have picked up the nuances of their nonverbal communication, while inferring meaning in the autistic person’s behaviour which is often at odds with what they were trying to communicate. Autistic people often miss nonverbal cues, and struggle with ambiguous phrasing because they don’t have all the same contextual information in mind.

With practice, monotropic people can often master complex skills like conventional communication and, say, driving. This process involves chunking — learning to understand things as unified wholes, rather than collections of disparate information. It stops feeling like rapid, effortful switching of attention between different things, when one attention tunnel can accommodate all these aspects of one larger focus.

When such chunking is not possible, it can be incredibly stressful and draining for a monotropic person to have to divide or constantly switch their attention between different things. It is likely that this kind of strain — what Tanya Adkin calls ‘monotropic split’ — plays a major role in many meltdowns and other effects of autistic overload, like burnout.

The Double Empathy Problem

Empathy is not magic. Recognising the emotions of other people requires an understanding of the cues that tell you how they’re feeling, and the internal experiences behind them. If those cues match up with what you’re used to seeing — and especially if cues and feelings match up with what you would do and feel — empathy is much more likely to be effective and accurate.

It follows that people with very different experiences and ways of expressing themselves are likely to have difficulty empathising with each other.

This is perhaps a conclusion that anyone could have reached with a bit of thought, and Jim Sinclair made a similar observation back in 1988, but for whatever reason, autism researchers and psychiatrists seem to have ignored this glaring flaw in their conclusion that autistic people lack empathy, for decades. Autistic scholar Damian Milton describes this issue as the ‘Double Empathy Problem’ in 2012 — empathy goes in two directions, and non-autistic people regularly struggle to empathise with autistic people. In the decade after, a whole series of experiments clearly demonstrated this in action.

While it’s most relevant to autism because autistic people have been thought to be weak empathisers, the general principle has wider relevance. It is worth pausing to note that with groups which are more dominant in a society, people outside of them generally get to hear quite a lot about their experiences and perspectives: everybody in a majority-white society hears about what it’s like for white people; everybody in a patriarchal society hears about what it’s like for men. In the same way, autistic people get much more practice understanding non-autistic people than the other way round.

It’s never just about autism

One thing many autistic people are tired of hearing is ‘your autism doesn’t define you’. Of course it doesn’t: nobody is defined by one characteristic, even though autism shapes every aspect of how I experience and interact with the world.

For all its pervasive influence on who we are, there is always much more to anyone, and there is no way to understand how someone’s autism affects their life without understanding other aspects of their identity, and how they interact. Most of the early descriptions of autism (and many of the later ones) were based on young white boys, and it shows.

Autistic girls and women have very different experiences, on average, from autistic boys and men — even though there is nothing categorical about the differences. There are boys whose autism has been missed or misunderstood for the some of the same reasons as many girls’ — largely because they have learned to internalise their difficulties, and try to blend in. Then again, sexism also directly shapes the experiences of women and girls — not least the sexism of people whose jobs should include recognising them as autistic. Gender nonconformity and trans identities (which are far more common in the autistic population) also complicate the picture.

Racism plays a huge role in how autistic people from racial minorities are seen, and cultural differences shape what autism looks like in practice. Neurodivergent Black boys are more likely to be seen as threats by white people, for example, and less likely to be greeted with empathy.

Finally, autism is part of a suite of related differences, physical and mental, which frequently co-occur, and are not always possible to separate. Anxiety is so prevalent in autistic people that non-anxious autistic people are almost unheard of, but it’s not part of autism. Depression is also very common in autistic people, probably because of how society treats us.

ADHD is more common than not, leading to speculation that it might be part of the same thing — yet it’s associated with some things that are so at odds with stereotypes about autism that each is sometimes overlooked when the other seems obvious. Something like a third of autistic people have learning disabilities, a figure which was once thought to be much higher. Hypermobility and EDS are strongly correlated with autism and other neurodivergence. Throw in ME/CFS, POTS and epilepsy, and it’s clear that a high proportion of autistic people are disabled in multiple ways. Most of these connections remain under-researched and poorly understood.

Above all, autistic people are humans: as diverse as the rest of the population, if not more so. Understanding any individual autistic person means getting to known them as a person; there is no autism without autistic people, and there are limits to how well it is possible to understand autism in the abstract.

As diverse as we are, though, we have collectively worked out a great deal about what autism means for us — and we have been patiently explaining it for decades, to anybody who is willing to listen. Thankfully that includes more people than ever, but there are still so many who have a lot of catching up to do.

Books

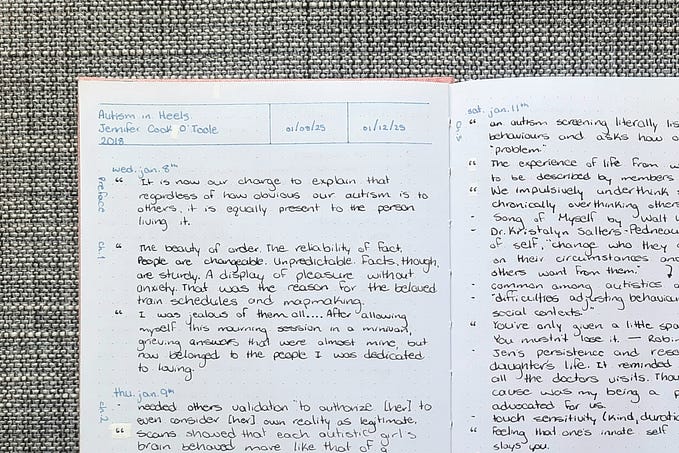

These are just the autistic-authored books I have on my bookshelf; many of them are excellent, but their inclusion is not necessarily a strong endorsement, because I haven’t read all of them. Here they are, alphabetised by author surname:

- A Different Sort of Normal — Abigail Balfe

- Underdogs — Chris Bonnello

- Empire of Normality — Robert Chapman

- Understanding and Evaluating Autism Theory — Nick Chown

- Autism in Translation — Edited by Elizabeth Fein & Clarice Rios

- Ten Steps to Nanette — Hannah Gadsby

- Wired Our Own Way: An Anthology of Irish Autistic Voices — Edited by Niamh Garvey

- Different, Not Less — Chloé Hayden

- Defend Sunlight: Illuminating Ways Through the Darker Times — Katherine Highland

- Stim — Edited by Lizzie Huxley-Jones

- Odd Girl Out — Laura James

- Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement — Edited by Steven K. Kapp

- Concepts of Normality — Wendy Lawson

- The Passionate Mind — Wendy Lawson

- Autism, Bullying and Me — Emily Lovegrove

- Letters to My Weird Sisters — Joanne Limburg

- The Neurodiversity Reader — Edited by Dr. Dinah Murray, Dr. Damian Milton, Dr. Susy Ridout, Professor Nicola Martin, and Richard Mills

- A Mismatch of Salience — Dr. Damian E. M. Milton

- The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Autism Studies — Edited by Damian Milton and Sara Ryan

- A Kind of Spark — Elle McNicoll

- Like A Charm — Elle McNicoll

- Show Us Who You Are — Elle McNicoll

- The State of Grace — Rachael Lucas

- M is for Autism — The Students of Limpsfield Grange School and Vicky Martin

- Perfectly Weird, Perfectly You — Camilla Pang

- Understanding Autistic Relationships Across the Lifespan — Felicity Sedgewick and Sarah Douglas

- Understanding Others in a Neurodiverse World — Dr. Gemma Williams

- What I Want to Talk About — Pete Wharmby

- Un-typical — Pete Wharmby

- Learning from Autistic Teachers — Edited by Dr. Rebecca Wood

On Being an Autistic Therapist — Edited by Max Marnau — is missing because I couldn’t find my copy, and for some reason so is Autism Equality in the Workplace — Janine Booth.